After having experienced vastly different office cultures in my career, I want to write out some of my thoughts on the impacts different aspects of office culture have on the productivity of engineers and how we work and collaborate.

Explicit Culture

Explicit culture is essentially anything in writing, and systemically enforced with incentives, about how people should operate in a workplace. For instance, if engineers know they will be evaluated and recognized based on the impact of their ideas, the speed with which they adapt, how much they raise the bar on quality, these create incentives to behave in corresponding ways. Everyone in the office is now trying to have a larger impact, show that they pivot quickly, and insist on shipping higher quality experiences.

I believe that something would not count as explicit culture if the people were not being evaluated against it, or if they were unaware that they were being evaluated that way. It needs to be both explicitly told, and explicitly enforced. Otherwise, the incentive does not hold. The environment would not be impacted by everyone working with this guiding principal in mind.

Implicit Culture

Offices can, on the surface, have no culture. That is, no written guidelines for how people should be operating and expecting to be evaluated. In these cases, there is just as much of a culture, but it is implicit. People who have worked in that office longer, or are higher up, are likely in a social circle that silently agrees on many aspects of how they are all handling their work. People coming into that office are figuring out these norms gradually and being pushed to adapt. This causes wasted time. What is worse is the implicit parts of the company culture might be counterproductive practices that would sound wrong if put in writing.

My Beef With Implicit Culture

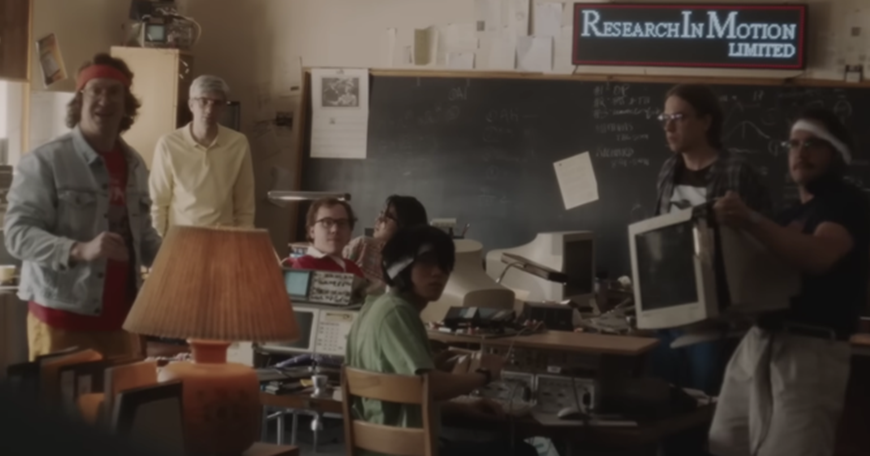

The first office I worked at had some implicit culture quirks that I hope I don't get sucked into again. These are all things that are liable to be find at many smaller software shops.

Two-way door technical decisions were preferred to be deferred to management and took a great deal of deliberation, the opposite of Amazon's Bias for Action. This created an environment where the people working in the code are regularly discussing easy things they could do in a week to drastically improve the product, while working on less impactful tasks for months on end.

Review meetings were presentations to the executive suite to get them to sign off on building something. This was so much different than the writing culture at Amazon, and the autonomy teams get in determining what they build. It is also much different than the way that AWS allowed me to loudly disagree with and push back against leadership to their faces, and get praised when I was correct in doing so. The implicit culture I experienced was far more interested in enforcing the company heirarchy in every respect, even in making engineering decisions.

Reviews at that company were a bit of a bad joke. Not because I was reviewed poorly, but because I had to game the system rather than be productive in order to be reviewed well. The metrics used included things like number of commits pushed, or number of tasks completed (not distinguishing 2 hour vs 2 week tasks). I am confident I wasted a significant amount of everyone's time gaming my numbers, although it did work and nobody stopped to sanity check. This was the exact opposite of the "Deliver Results" mentality, and I do not miss it.

Response and availabilty expectations were practically anarchy, with urgent emails sometimes drowning in Outlook inboxes. The only teams I was on at that company used email and skype, and later Slack. I worked with people there whose team mainly used Microsoft Teams, but I never downloaded it while I worked tere. This also led to a culture of talking to people at their desks face-to-face, and/or firing nerf guns to get attention.

Similarly, risk was avoided heavily, since employees were punished much more for a failed experiment than extended periods of quietly completing tasks that provide minimal business value. In fact, the risk of job loss was sinificant enough that many employees were the only person who knew how to maintain or fix a part of the system, and they refused to share their knowledge. These are symptoms of management giving engineers counterproductive incentives. Those incentives eventually formed emergent aspects of the company's culture.

Finally, social circles influenced every aspect of the implicit culture. A good portion of people were in an older group, both in age and seniority, close enough to joke with each other in ways that HR wouldn't want to know about, and regulraly discussing sports betting. A younger portion of the company shared neo-dadaist humor, interests in gaming, and a shared sense of disillusionment. A few people worked almost exclusively in their own quiet silos. In contrast, AWS made us all too focused on work for any significant amount of hobbies or humor, and we had explicit incentive to get along with as many people as possible, which I suspect discourages closed cliques.

Changing Culture Yourself

I have some experience from being a startup CTO being able to shape a budding culture from my experience and ideas. Being near the top comes with a great deal of ability to influence. In AWS I was able to greatly influence the teams I was on in their development processes, meetings, and how they interface with other teams. But everything was restricted to remaining within the scope established by Leadership Principals.

The impact you can have on a company decays exponentially with the number of layers above you. It takes a great deal of specific soft skills to influence people around you enough to expand influence.

What I Want To See

I value having explicit culture over not. Putting in writing what is happening puts the trash on display. There are some things I have not experienced explicit culture address that I would like to see addressed.

Incentivize Assisting Peers

Many offices like like to rank everyone in a given role against each other on various metrics, and none of those metrics accounts for how much someone helped or hindered others. If I am incentivized to be ranked highly, then I should refuse to help peers solve their issues or grow their skills, so that they somebody who is struggling does not risk competing with me. I may even feel incentived to make decisions that I believe will make things harder for my peers but not for me. This can be bypassed by adding value to everyone based on estimating how much mentoring they did, or how much they improved development processes, accounting for the larger productivity impact they have had.

Make Managers be Managers and Engineers be Engineers

AWS has shown me the astonishing power of engineers making engineering decisions and managers making management decisions. I have seen this in the form of managers and even higher up leadership discussing an issue then saying they need an engineer to make this decision. They are encouraged and rewarded for doing this over making these sorts of technical design decisions themselves as someone who is not actively working on the infrastructure themselves. This results in far better decisions that account for issues and quirks of the existing system that managers would not have thought of.

In contrast, I have had five managers now who all very much tried to make the technical decisions themselves even with very old or limited technical backgrounds. Almost every time, engineers being given work from them were well aware of the glaring issues preventing these decisions from actually working. This gave engineers a lot of extra work to demonstrate how and why this idea does not work, or to waste a great deal of time delivering something that does not work and perhaps gets rejected by the customer who now refuses to pay. We knew every single time. The managers did not.

Incentivize Getting Along

One thing I think managers across the industry are getting wrong is defending the office asshole. I am talking about the one middle aged white man who has received feedback from 30 to 50 people that they do not like working with him. I believe managers are often holding onto these people, sometimes even upholding them as a standard because, as I strongly suspect, I believe they look good on paper due to the negative impact they have on every other engineer around them. Their value is an optical illusion. Removing them from an office will probably improve the performance of the nearest 20 people by a standard deviation, and makeup for removing them several times over.

Encourage Engineers Identifying Problems Themselves

Engineers tend to identify problems long before managers do. Managers see production blowing up once a high profile customer is screaming. Engineers see production blowing up two months ago when they were discussing the completely unhandled issue the system could encounter under fairly realistic conditions. There is exponential value in managers getting their projects from engineers, with managers verifying the business value, and figuring out the high level planning.

Ultimately, Progress

The point of everything above at the end of the day is delivering the best possible customer experiences, maximizing how much people's lives are inproved by the services we create. The challenge here is a matter of getting many people onto the same age on how to accomplish that.