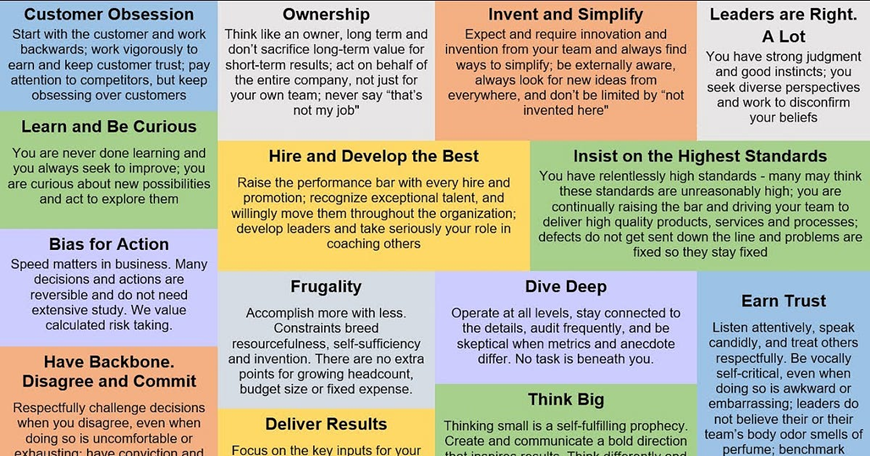

AWS culture is highly explicit, that is written out, rather than unwritten rules. Everything is broken up neatly into Leadership Principles that are publicly available. I will go over all of those one at a time, including my perceptions of how I saw them reflected, used well, and used poorly, if not outright abused. Since the culture is written this way, I need to explain it this way.

I want to highlight that these are not just vague company ideals that were put into writing. They are enforced through hiring and performance reviews being based around how well everyone fits into them. That makes them far more than a suggestion, but something everyone is the office is pressured to focus themselves on. This enforces the explicit culture, ensuring it can be found everywhere. From my experience working and talking to people from many teams, and from other parts of AWS like S3, MSK, DynamoDB, the culture is consistently found everywhere. This is to me an impressive feat to scale up a single workplace environment.

Customer Obsession

This is straightforward and incredibly important for any software development. We are essentially engineers who specialize in creating services rather than goods. Those services have value from utility to users. Maximizing that utility intentionally from day one maximizes value. Whenever we start designing something, we start with writing out what the customer needs, what they use this service for, the business value produced, the demographics and special needs of the customers even.

When I think back to the days when I was maintaining utility software, there was a product facing employees at utility companies, and a product facing individual utility customers. Employees at utility companies are older, less tech savvy, had lower resolution monitors at their work than we had at ours, and apparently disproportiately reliant on screen readers. UI decisions either started from this, or face costly redesign if they did not. User workflows were either clear and intuitive, or skyrocketed customer support and training costs. On top of that, accessibility misses, or workflows that fundamentally failed to meet their business requirements resulted in angry customers who could never be used as a reference. Producing the wrong functionality means customer needs failed to be understood, which means in hindsight the very first step was a failure.

Every new design at AWS starts with fleshing out an understanding of customer needs. Arguments for customer workflow impacting decisions are made just about exclusively from customer experience and needs. This point of office culture prevents chronic cases of months of engineer time being thrown away.

The only downside of this principle I have seen was some one of cases of people calling things they did not agree with not customer obsessed inappropriately in order to get their way. This is where some people, especially fresh graduates, will fold quickly, but most people will argue back and shut this down.

Ownership

Ownership is my favorite part of AWS culture and frankly what kept me going. Engineers do not simply take on a project, or a portion of a project, or a feature - They own it. In other words, they are responsible for everything from design, implementation, testing, and deployment. That doesn't mean doing all the work yourself, but at least making sure the work is all getting done and the right things are being worked on by the right people. It means if you dependant on another team, you are encouraged to push that team and their manager and their manager's manager. You will either get the work you need done, or someone above you pushes back your project, and your manager rearranges priorities top-down. Either way, you are fine, and not stuck working on something that cannot be completed due do dependency, or blamed for being blocked. In some ways, this principle pushes engineers to be assertive and loud, therefore impactful and ultimately much more valuable.

My perception right now is that criticism against this principle is misguided. It is mostly complaining about not knowing what to do when being told to be more independent, or not wanting to be blamed for failing to deliver. The stories are often from people who briefly worked at AWS and were repelled by this culture. I have seen several engineers come and leave within a year, having a computer science degree, having technical and coding skills, but being in the mindset of doing the work they are told, and not in a mindset of speaking up about issues directly in front of them, or questioning if the work they are given can be designed better, or pushing teams they require effort from. I believe the software industry as a whole is fundamentally unfit for engineers who want to be given work that they are rewarded for completing well as given. Far more creativity, social skills, and sheer confidence are required to have a much larger impact and deliver far more. Virtually every project or task in this entire industry has opportunities to deviate from the original plan to deliver more value in the same amount of time.

Invent and Simplify

This is mostly encouraging us to really challenge constraints, question assumptions, and generally make the work around us more productive and valuable. This is another part of the culture of working autonomously, and contributing your own ideas rather than simply completing tasks. Being encouraged to think and behave this way often had a large impact on how I even think about my work. When the EBS performance on-call shift was excessively brutal with many inactionable pages, and long manual processes, I was able to take initiative to drive many solutions that sped us up a ton and avoided time waste. There were implementation tasks I was given, like tuning alarms, where I was able to do some of my own research, and deliver even better solutions than anyone else around me had ever suggested.

On the other hand, quietly accepting every design desicion around you makes you percieved as not being impactful, not nearly as valuable. This is an accurate assessment for the business really. Again, I saw some great coders not survive in AWS because being there simply is not as much value in being the best code writer compared to being one of the people who actively shakes up their environment.

Are Right, A Lot

This was a strange one to me for a long time before of how vague its name feels. It is not intuitive to me how this impacts day to day interactions. From my experience, I think the main thing that really stands out to me here is one sentence from this principle: "[Leaders] seek diverse perspectives and work to disconfirm their beliefs". The biggest impact I have seen of this leadership principle is the culture of decisions being reviewed and made while calling out the alternatives. Design documents are opinionated and propose a single solution, but there is always a list of alternatives and some points with some data on the pros and cons of other decisions. If there isn't, everyone jumps to comment on this, and managers ask for a more complete draft. Every time a decision was made within EBS, even if I wasn't involved in it, I could go find the alternatives in writing somewhere. This is a lot different than someone having the power to make a decision and being encouraged to do so entirely on their own.

Unfortunately, sometimes it felt like decisions from the top or close to the top had extremely flimsy or redacted counterarguments or data. Infamously the full return to office decision from the "S-team" has no data or reasoning behind it, at least accoring to a handful of managers I talked to about this.

This principle seems to be evaluated by results. It is a negative when a decision turns out poorly, even when arguments and data were widely peer reviewed, which is unfortunate, but is life. Conversely, forced one-person decisions that turn out well anyway are reviewed positively. I think this is why the principle is named after being right, rather than being named after seeking diverse perspectives, although my focus is always on the latter, since it maximizes the odds of making the right decision. I personally believe there would be merit to a greater focus on seeking diverse perspectives, for instance a successful decision made with no opposing ideas considered involved some degree of luck and shows a lack of discipline that I think is more likely to go wrong later than someone who was wrong despite significant review and input.

Learn and Be Curious

This is the most joked about because new hires are always given this in reviews as their strength. From what I saw, this is probably one of the hardest ones to get negatively reviewed about. You would probably have to stand out as someone who does not do additional research, and constantly needs to ask for help on things that should have been been easily answered independently. I think this only really exists to remind us to be using our resources, otherwise we might forget what we are capable of.

Hire and Develop the Best

This is mostly about fostering a culture of mentoring, helping peers, and spreading knowledge. There is more to it for people involved in hiring specifically I'm sure, but the regular impact I saw of this was mostly people being given kudos for effort put into lifting up others around them. In a way, I feel like this principle is trying to encourage giving people credit for the additional work done around them due to them.

Insist on the Highest Standards

I love being encouraged to be vocal about wanting more robust processes and designs whenever managers are pushing for quick and dirty and going to blow up in their face later. I do not miss talking to coworkers about how we know full well we are working on the wrong things, or working on things that we know will be undone and backtracked, then feeling like a slep deprived messiah later. I am biased since I naturally complain anyway.

This principle also encourages standards like taking on about 25% more work than can be done so that we typically land on delivering 80% of what was planned. This applies to 2-week sprints and to 1-year plans. I think this is common across the industry now, and there is some science backing it. Positive feedback around this principle comes from advocating for processes that will push us further. Unfortunately, this principle is also a culprit behind a lot of excessive work hours, intense operational load, and heroic efforts.

Think Big

What this principle essentially has come to mean for me is that we are all expected to think like inventors. We are encouraged to be trying to come up with solutions to any problems we see with the products we touch or our team's processes. We are encouraged to pull in our own research. We are encouraged to push back against bad ideas, be vocal about our ideas, and overall be proactive in identifying and solving problems. This principle pushes us to never become complacent, passive actors in the workplace, letting everyone else make the decisions. We are not allowed to do that here.

The upside of this that I really appreciate is being rewarded, not punished, for being as proactive and vocal as I want to be. I never have to sit around sulking in how terrible my team's processes, operations, and project management are. If our meetings, on-calls, or sprints are a mess I can often take up largely fixing things myself. The most blatant downside of this is that a lot of engineers will see this culture as unwelcoming, or inaccessible. If you don't recognize the opportunities, and don't understand how much the culture allows you to speak back to managers and leadership, then all of the problems around you will just look like problems that you assume need to be put up with. The intensity of issues most teams deal with at any given time would scare away anyone coming into it with the wrong mindset, and without enough spare willpower.

From what I have seen in reviews, you are considered weak at this if your ideas you propose do not generally pan out, and the impact ultimately fizzles, even if it was just a lack of buy in from your team that held you back. This is one of the places where politics come in: People around you need to follow you, and be on your side in general.

Bias for Action

The main impact this has is encouraging everyone to make low-cost (i.e. easily reversible, or two-way) decisions quickly without needless meetings or analysis. Minor implementation details can be made by the person writing the code on the fly.

This is the opposite of how management often works in tech companies. Engineering decisions are generally made by managers, and engineers have to attempt to argue against decisions made without crucial information.

Frugality

I recall one of the principal engineers in EBS saying something like the best designs are so simple they look like they would have just been obvious, even though they were not. The best designs are relatively cheap in development, infrastructure cost, and maintenance. This includes anything from complex services to minor implementation directions. This principal is just a solid guideline for good engineering. Something has hone wrong at an office that routinely overdesigns and spends extra money delivering not extra value.

Earn Trust

The concept here is pretty simple. Engineers and managers are rewarded for demonstrating that they can deliver (or over-deliver) on external promises, fix things quickly for their customers when something breaks, and work with the customer to meet their needs and alleviate their anxiety effectively.

In practice most of the time our customers are other teams as we build a great deal of internal tools. We are often judged by decisions we made that impacted the other teams, with other managers seeming often eager to praise a team that helped them. At some offices, recognition is rare, and some companies have reputations for teams fighting, being unable to collaborate. I suspect Earn Trust is driving the closeness of teams since everyone is explicitly incentived to build positive connections.

Dive Deep

When things go wrong, or a problem is identified, we are encouraged to go all the way through the root causes of an issue, be it technical or operational. We are strongly discouraged from glossing over it. Sometimes we realize that we can ask for service improvements from other teams to boost our team, or even discover work other teams can take on to improve the system at large. This feels much different than management that wants to sweep issues under the rug to make themselves look good, or encourage engineers to just keep building the next thing as fast as possible without additional thought that leads to groundbreaking innovation.

Have Backbone; Disagree and Commit

This idea makes perfect sense from the perspective of building many services that all work together over time as everything changes. Many largely independent systems need to be on the same page, and in some ways moving in the same direction. This requires leaders to make decisions, and once final, for engineers to follow. Ignoring decisions you don't agree with is sabotaging your peers after all.

Now while this principal makes perfect sense in theory, in practice this is a disappointing principal. I have seen people evaluated on this more or less around being willing to admit they are wrong in discussions, and being able to rework their own proposals. Usually when this principal comes up in conversations it is about decisions from high up that are opaque and appear to lack both data and diverse perspectives. It usually means "tough shit".

This principle was the justification for monitoring office attendance after 5 day RTO, which most who I have spoken to believe is about causing attrition and utilizing tax benefits around commercial real estate use. That seems like a good example of this principal going wrong to me, at least from a ground view.

Deliver Results

This is self explanatory. You get graded here based on how much you accomplished relative to the portion of the year you were working, and relative to your peers. This is an explicit culture of judging people based on what they actually accomplished, rather than how we feel about them. I appreciate how this one skews performance reviews towards what I actually accomplished, and steers it away from things like the number of commits I pushed, or the number of days I clocked in before 9.

Strive to be Earth’s Best Employer, and Success and Scale Bring Broad Responsibility

As far as I can tell, these are jokes. I have not seen these factored into annual reviews, not even for managers (and yes I saw some of those uncensored). Nobody in the office believed that leadership was genuinely following these in practice, so it is not clear if or how anyone is evaluated based on these. I have not seen these impact how anyone in the office behaves.

My Thoughts Overall

AWS feels like a workplace that actively wants a high rate of turnover. It wants people to stick around only if they are suited for thriving in a highly competitive cutthroat environment. People not suited for this environment will burnout until they can no longer perform, where those who do fit in here will thrive comfortably. The former group will work long hours with no work-life balance to keep themselves employed. The latter group is plenty productive in this environment to not need to overwork themselves.

In some ways, the incentives of engineers and business naturally align. Both are incentivized to deliver the highest quality and most accessible customer experiences they can, to innovate in ways that carve out and dominate markets. Many of the leadership principles reflect shared incentives. But some incentives will fundamentally conflict, not because of the company or its culture, but intrinsic to these roles. Engineers have incentive to have a work-life balance, to be comfortable and included in an office, in ways that employers can compromise on or pay lip service to depending on job market pressure, but it is not necessarily their incentive.

Amazon's explicit office culture is perhaps brutal for engineers but powerful for maximizing innovation, and providing superior services that can dominate industries. It is an impressive feat, and also a painfully stressful environment to exist in that only few grow comfortable and truly thrive in without sacrificing their physical and mental wellbeing. And yet as an engineer, there are many aspects of it I love having and would not want to lose working elsewhere.